The Sociology of rural Modernity

Since the era of French positivism in the late 19th century, the topos of Mediterranean underdevelopment had assumed a firm place in the sociological canon. The Mediterranean region thus became the original primitive “other” against which industrialized Northern Europe defined itself.

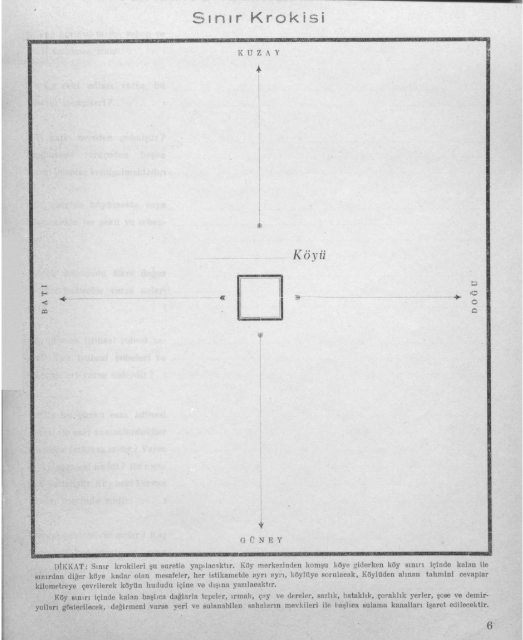

Defining “backwardness” became not least a question of which research techniques and methods were used in the process. In the early 20th century, the French réforme sociale school achieved particular prominence in this regard. The observation of family clan structures in the societies and communities of the Mediterranean developed into a methodological approach through which sociological theory sought to take advantage of the new infrastructural accessibility of isolated regions and pursued the fantasy of using new technologies to quantify social problems via statistical methods. In this regard, these scholars never understood themselves as neutral observers. Instead, they conceived of their role as opening up isolated regions to the outside world through their research and relating the specific challenges faced by these areas to more universal social problems.

This ingénerie sociale school had a broad influence on the emerging field of Mediterranean social science. It defined new research methods and agendas and contributed to a new village sociology that understood itself as a motor for societal change.

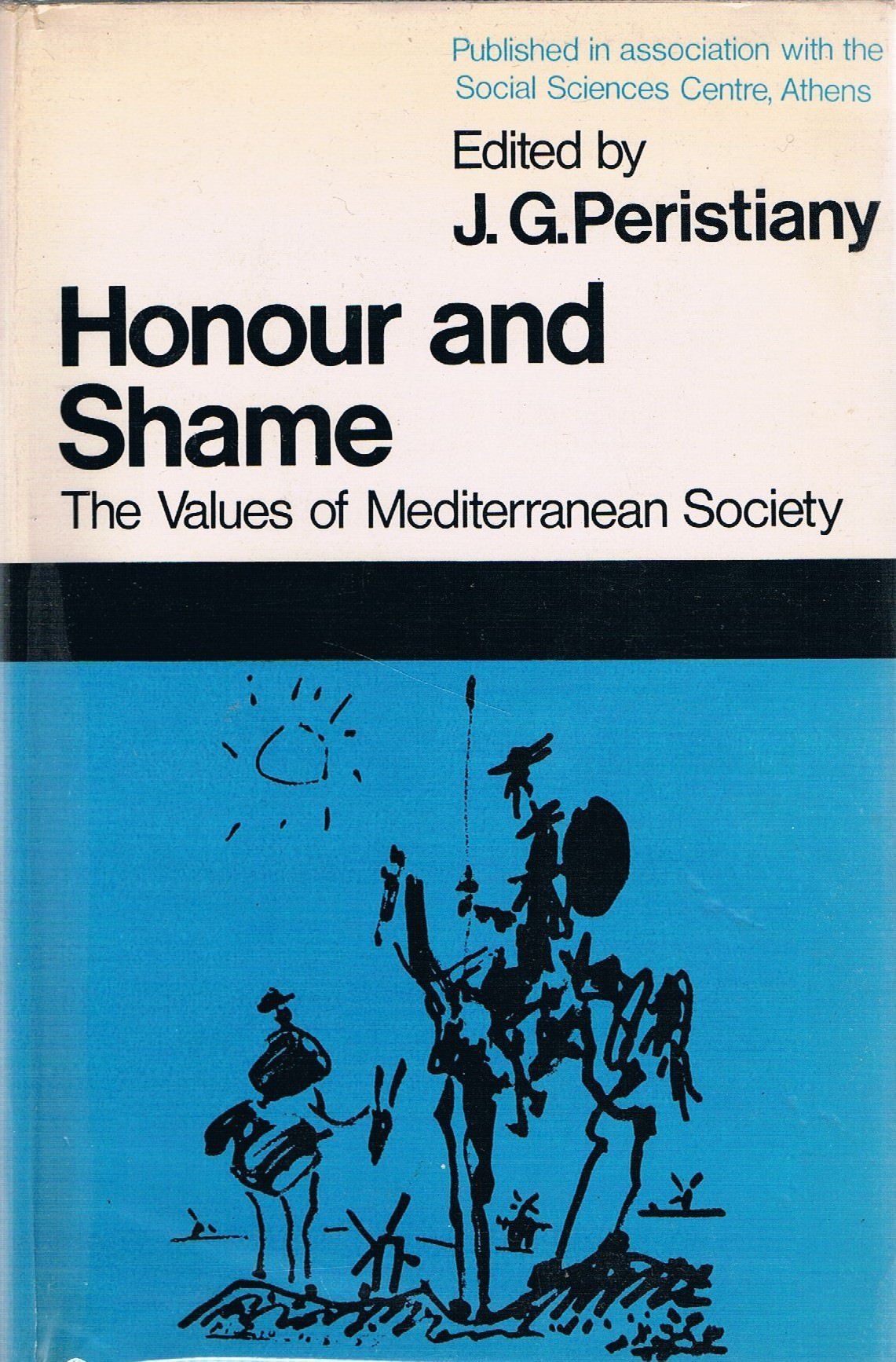

In the post-war period, the Mediterranean remained a popular location of research for the social sciences. In the early post-war decades, ethnology assumed the mantle of the Braudelian Mediterranean topos and examined the Mediterranean basin as a closed cultural zone.

At the same time, this type of ethnology upheld a large part of the structural-functional legacy of colonial research. From the very beginning, the documentation of small village or clan communities was emphasized.

The project investigates the conceptual, methodological, and personal continuities across these different fields of Mediterranean social science and their role in perpetuating an image of Mediterranean underdevelopment.