Expertise as a cultural technique in the rural context

(Verleihung des Kulturpreises 1970 an Prof. Fritz Baade, Stadtarchiv Kiel, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

Rural modernization policy in Europe was closely intertwined with the aims of “internal colonization”—namely, a country’s efforts to open up, control, and develop its hitherto backward rural areas. In Germany’s eastern territories, for example, many such projects were initiated towards the turn of the twentieth century, with agricultural experimentation and training stations being the most visible manifestations of this approach (following in the footsteps of the first such station, which was established in the Saxon town of Möckern in 1851). The agricultural cooperative movement also followed in this tradition in the early twentieth century.

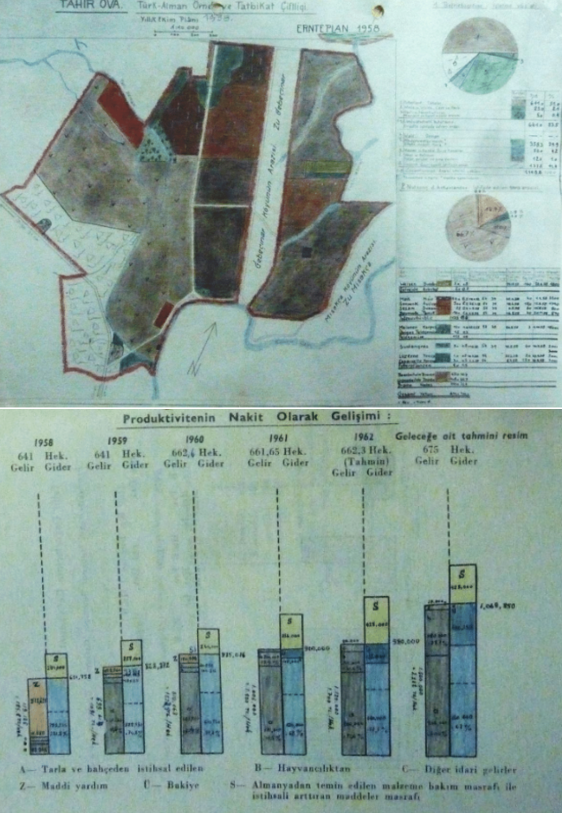

Both within the context of the prevailing crypto-colonial economic policy of the interwar period as well as new programs to boost productivity after the Second World War, similar institutions promoting rural modernization were also established in the Mediterranean region. Model farms were opened in Turkey and Tunisia, while in other countries the focus was placed on establishing programs to develop rural cooperatives with the assistance of Western European advisors. From a German perspective, numerous scholars who had gone into exile in order to escape political persecution at the hands of the Nazis were engaged in such projects.

The model farms were not only intended to be a vehicle for spreading technological innovations and imported US or European agricultural machinery. They were also envisaged as a means of promoting a general commercial spirit or specific skills such as agricultural bookkeeping techniques.

Increasingly, the model farms were also thought of as motors for the transformation of local and national agricultural practices: new livestock breeding projects were not only supposed to bring about gradual improvements to breeds but were also meant to establish the development of new breeds of cattle or sheep as a new commercial focus for local agriculture.

Such projects, however, also made Western “experts” dependent on the cooperation and knowledge of the local population. It is precisely these dialogical dimensions of the resultant reciprocal learning processes as well as the social conditions of these knowledge flows that will occupy a significant portion of this sub-project’s attention.